Predictive Paradigm: The Octopus of Attention (pt. III)

Understanding the Interplay of Attention and Prediction in Human and Artificial Intelligence

When we think of the mind as a predictive system, you might picture something like a robot, methodically processing data without emotion. But there's clearly more to us than that. There's a vibrancy and energy to human life that any accurate theory of the mind must capture. It’s this spark—this dynamic essence—that turns our routine processing of data into a vivid life of thoughts, emotions, and actions.

Attention is key to transforming this mechanical view of the brain into something more lifelike. It brings the brain's predictive engine to life, guided by our desires and focus. It helps us handle the predictable and adapt to the unexpected.1

To fully appreciate how attention works, we need to recap the basics of predictive processing, the brain's forecasting mechanism. We've previously explored the predictive process in this series (here, here). To summarize, imagine your brain as a brilliant meteorologist constantly forecasting your experiences. Your brain uses the past to predict what will happen next in every aspect of your life, from expecting the sun to rise to anticipating the first sip of your morning coffee. When these predictions are correct, your day proceeds smoothly (and your mind is free to wander aimlessly). However, if predictions fail—say, if your coffee tastes bitter—you notice instantly. This error grabs your attention, prompting your brain to adjust its predictions to avoid future surprises.

In other words, prediction errors attract attention so that we can learn by discerning which components of the situation we got wrong. Is there a new barista? Did we drink the coffee an hour after it was made? Which factor should we adjust? This learning process identifies the root causes of errors. In the world of AI, this is the backbone of model training, called backpropagation. All that's needed to train a large, highly intelligent AI is the following:

Start with a random model.

Provide the model with input data.

Allow the model to make predictions based on what it sees.

Correct the model by providing the right answers (usually done by a human or a pre-trained model).

Have the model focus on the error (the difference between its prediction and the actual answer).

Let the model adjust its weights based on this error.

Repeat this process a billion times.

And this is no different from how a child learns colors, reading, and the art of empathic relationships.

To summarize: In this basic view, prediction drives attention—more precisely, prediction errors attract attention. It’s like a teacher scanning a sea of correct answers but stopping to circle an incorrect one in red. Humans and AI alike learn from these unexpected events that don't match our predictions, improving future forecasts.

However, the relationship between prediction and attention isn't just a one-way path. Let's explore the flip side: how attention shapes predictions.

While errors can grab our attention, we have significant control over our focus. We can direct it, influencing what the brain predicts next.2

If you decide, for example, to improve your cooking skills, you focus on recipes and techniques. And soon, your taste and smell sharpen. Food, cooking techniques, and culinary tricks start popping up in everyday conversations, books, and even your social media feeds. Your attention to specific details reshapes your brain’s predictive model, making it more attuned to cooking.

Achieving the right balance between attention and prediction brings us into a state of flow, where time seems to fly and every action feels effortlessly precise. Flow is what happens when our predictions and attentions are so well aligned that they drive each other forward, creating a smooth, uninterrupted experience.

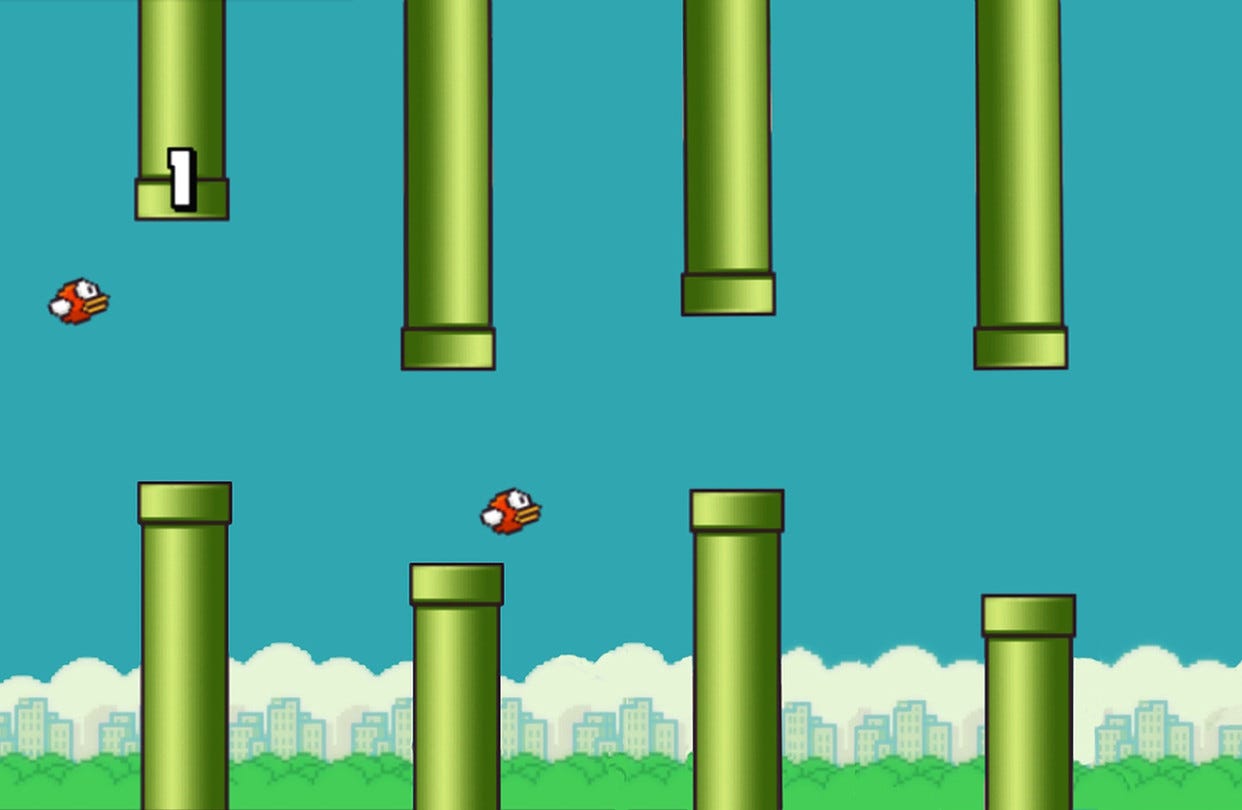

Take the game Flappy Bird, for example. It's simple, but fiendishly addictive. So addictive, in fact, that its author decided to pull it from app stores to save humanity.

As you play, your entire focus narrows down to the bird's motion and the upcoming pipes. Your brain predicts the height and timing needed to pass through each gap based on your previous attempts. Each tap is a test of your attention to the bird's position and your prediction of gravity's pull. Success leads to deeper immersion, locking you into a loop where attention and prediction perfectly complement each other, making the game deeply engaging and hard to put down.

In this loop, attention to the immediate obstacle (each set of pipes) guides your taps, while your predictions of the game’s physics refine your responses. The better you get, the smoother your gameplay, and the more you experience that state of flow, where your actions and awareness are in sync. When you make a mistake, the error hurts.

Building on our understanding of attention and its impact on our experiences, it's fascinating to consider the theory proposed by Andres Gomez Emilsson, which suggests that we don't just have one general "attention center" in our brains. Instead, Emilsson posits that we have about seven distinct centers.

Imagine you’re at a busy street fair. One attention center focuses on the vibrant colors of the stalls, another tunes into the music, while another alerts you to the smell of food. Each center processes its stream of information, contributing to a rich, multi-sensory experience.

On the other hand, a person immersed in a classical music concert is likely utilizing multiple attention centres to discern various instruments and harmonic components. Crucially, this means that our attention is not a singular beam but rather a multi-faceted octopus, with each tentacle exploring its own attractor space.

Emilsson’s theory also sheds light on conditions like narcissism, which he describes as a disorder of attention. In narcissism, two or three of these attention centres are excessively focused on the self, making it difficult to shift focus to others’ needs. This over-focus on self can disrupt social interactions and relationships.

Emilsson encourages an exercise: try to discern your individual attention centers. For example, when listening to music, focus only on the bass tones or the high hats, switching your attention from one to the other. Or while looking at a landscape, shift your focus from the shapes of the trees to the colors of the sky. This practice can enhance your sensory appreciation and improve your control over how you direct attention, offering deeper insight into how your mind orchestrates focus across different stimuli.

My favorite time to study attention is while driving a car. It’s possible to shift from an active mode of doing the driving to observing the driving. After 30 years of driving, my feet, my hands, my eyes, my processing — they are all coordinated and steer the car effortlessly. And I can shift focus among the multiple attention centres to watch their interplay.

The idea that we have multiple attention centers that we can focus independently is highly applicable to relationships. Often, people act as if they can only pay attention to either themselves or the other person. When they listen, they lose touch with themselves. When they talk, they lose touch with the other. This leads to a transactional view of relationships, making them seem like a zero-sum game. Listening is seen as a service to the other at the expense of oneself. But if we have multiple attention centers, it means we can focus on both the other person and ourselves. That’s where connection appears—in the interplay of the inner and outer. In this framework, relationships are valued as a positive-sum activity. Try it next time you talk to someone: Pay attention to both of you. It’s magical.

Interestingly, modern LLM architecture reflects this. The idea of multiple attention heads, introduced in the seminal paper "Attention Is All You Need," has been crucial in advancing AI technology. Instead of using just one attention mechanism, the Transformer architecture uses many attention heads that work in parallel. Each head looks at the input data differently, with its own set of parameters. This allows the model to focus on various parts of the data simultaneously, helping it understand and process information from different perspectives.

This expanded view of attention can completely transform our lived experience. Consider the following idea:

Johnson asks us to watch where our attention typically resides. Is it on our thoughts, worries, the external world, our bodily sensations or emotions? Or other categories altogether? The "homebase" for our attention can significantly influence our quality of life.

People pleasing is a pattern of attention.

Obsessive thinking is a fixation of attention.

Rumination is a looping of attention.

Curiosity is an expansion of attention.

Gratitude is a reorientation of attention.

Resentment is a fixation of attention.

Victim mentality is a trapping of attention.

Codependency is an entanglement of attention.

Guilt is the weight of attention.

Regret is a dwelling of attention on past prediction errors.

But how does one exit these difficult patterns?

Johnson suggests that focusing on the flow of our emotions, rather than our thoughts, can transform our inner experience. Observing our emotions like a river flowing through us—without trying to change or judge them—can lead to a peaceful yet vibrant state of mind. This approach contrasts with the exhausting cycle often caused by overanalyzing our thoughts.

Our brain's predictive process is like a continuous loop: we predict our next emotional or mental state based on our current focus, which then shapes our experience and influences the next prediction. For example, focusing on anxiety about an upcoming event can make us more alert to problems, perpetuating our anxiety.

However, if we shift our attention to simply observing our emotions, we can break this cycle. This passive observation allows us to experience our feelings without being controlled by them, changing the nature of our predictions and improving our mental landscape.

Try a simple experiment: over the next few days, consciously direct your attention to different areas—your thoughts, external sensations, or your emotions. Notice how each focus impacts your mood and mental state. (Remember - with your focus, you are redirecting your predictions.)

Then go a level deeper: pay attention to the fluid boundary between thought and emotion. Notice the smooth, gradual transition between them. They are of the same fabric.

And deeper: Notice that the way you apply attention is as unique as a fingerprint. Some people lay attention like a bear's paw, others like a needle, a magnifier, or an eagle's eye. There's fiery attention and icy attention. There's the soft veil of attention and loving attention. We continuously bring our habit into the picture, rarely aware of its influence on our days. Hence another useful exercise: Bring your attention to how you attend. To build a vocabulary of the possible varieties, try QRI's Qualia Mastery.

In the next post in the series, we will shift toward the concept of intention and how it interacts with attention and prediction to shape our lives.

Speaking of the unexpected, let's clarify the difference between attention and intention. Intention sets our goals, like deciding to climb a mountain, while attention keeps us on the path, noticing each rock and root. Intention and attention are different brain processes altogether (with intention involving the prefrontal cortex and attention leveraging the thalamus and parietal lobes), and we'll save intention for later.

Here lies one of the greatest mysteries of the human experience: how the autonomy of focus works, and why it doesn’t feel mechanistic at all.

"Flow is what happens when our predictions and attentions are so well aligned that they drive each other forward, creating a smooth, uninterrupted experience."

Interesting way of viewing the flow, makes a lot of sense!